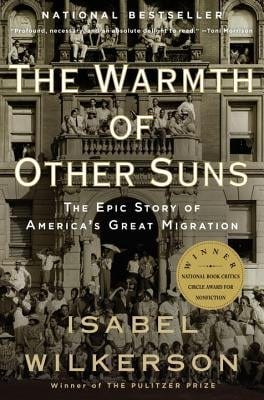

'The Warmth of Other Suns': American journeys

Isabel Wilkerson tells the story of the Great Migration.

This post contains an affiliate link or links. If you use a link to buy a book, I may earn a small commission. You can find all the books that have been featured in this newsletter in my Bookshop store.

I’ve spent much of Black History Month engrossed by a book I’ve long meant to read: Isabel Wilkerson’s “The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration.” The title matches the topic wonderfully; I get this mental image of people standing in the South and turning their faces to the North or the West, imagining better lives for themselves and their descendants. They make their decision, pack their things, and go.

During the Great Migration, Black people left the South by the millions: an estimated 6 million over 60 years, a prolonged movement noticed at first only on the individual level. It began shortly after the start of the 20th century and ebbed only with the end of official segregation. “By the time it was over,” Wilkerson writes, “no northern or western city would be the same.”

Wilkerson concentrates on the middle part of the migration, choosing two men and one woman to illustrate three of the main routes Black people took out of the South. Ida Mae leaves Mississippi’s cotton fields for Chicago in 1937. George leaves Florida’s orange groves for New York City in 1945. Robert leaves small-town Louisiana for Los Angeles in 1953. Wilkerson meticulously traces their lives from childhood through old age and shows how their stories are not just Black history, but American history.

Wilkerson is herself a child of the Great Migration: Her mother left Georgia for Washington, D.C., where she was given a spot on a second cousin’s sofa.

Soon afterward, she performed a ritual of arrival that just about every migrant did almost without thinking: she got her picture taken in the New World. It would prove that she had arrived. It was the migrant’s version of a passport.

Throughout “The Warmth of Other Suns” — informed by more than a thousand interviews and copious data and research — Wilkerson draws similar parallels between Black Southerners and immigrants fleeing unsafe situations. Both faced persecution and physical danger if they stayed. Both had to overcome significant barriers to departure. When they got to their destinations, both were burdened with stereotypes. Wilkerson notes of the Black migrants, “One myth they had to overcome was that they were bedraggled hayseeds just off the plantation.” In fact, they not only represented the most educated cohort of the Black population they left, but also had higher levels of schooling than many of the white people they now lived alongside.

And like immigrants from the world over, Black Southerners found that the Promised Land was not so promising after all. Ida Mae and her family endured subpar housing for years in Chicago; wherever Black people settled, white people responded with fury or flight. George found himself repeating his journey endlessly, working on the trains that had taken him North, relegated to segregated cars and unable to advance even after decades of service. Robert had his illusions shattered before he even reached California, as motel after motel denied him lodging, forcing him to sleep in his car on his way to becoming one of Black L.A.’s most sought-after doctors.

Yet they didn’t go back, even as they grew apart from their families of origin and their children grew up partial strangers, with different customs and perspectives and accents. As hard as their lives could be, these were lives they had chosen, rather than lives that had been chosen for them. Their migration was, Wilkerson writes, “the first mass act of independence by a people who were in bondage in this country for far longer than they have been free.”

I read this book several years ago and it was profoundly eye opening. As a white person I’d never heard of the Great Migration or the difficulties faced by the people who chose to move. Thank you for featuring this book. It’s a good read.

IIRC, I listened to this one as I commuted to teach in Albany and Corvallis a few years ago (pre-pandemic). It's incredible, and incredibly read by the great Robin Miles (https://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/how-a-great-audiobook-narrator-finds-her-voices - a NYer profile of the narrator!), and I was and remain furious that I didn't know much of the reality before I was an adult.

The city & state I grew up in were shaped by enslavement (the Missouri Compromise 🤢), the Civil War, **and** the Great Migration, particularly during WWII, and we learned nothing about it but the name in history class in high school (and I MAJORED in history in college at Mizzou?!?!). ANYWAY, so very glad this book is available to students and teachers, at least in states that don't ban it. Reminds me to give it to my Missouri and Kansas-dwelling niblings and their parents. Just in case they might want to know things before, you know, they turn 40.