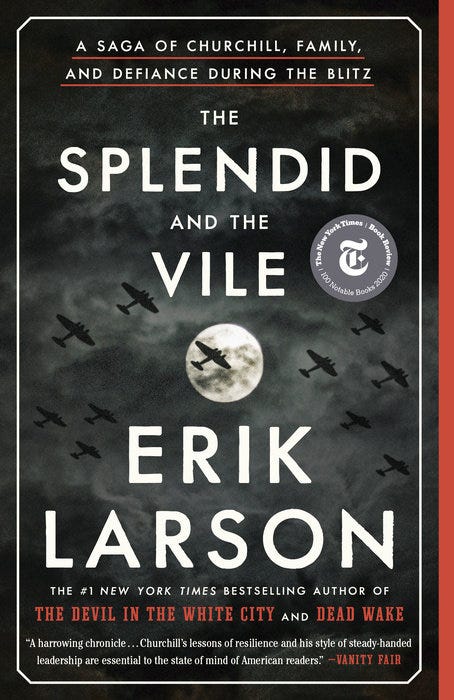

'The Splendid and the Vile': World War II history

Erik Larson provides an illuminating look at one of England's darkest hours and the man who refused to go gently into the night.

This post contains an affiliate link or links. If you use a link to buy a book, I may earn a small commission. You can find all the books that have been featured in this newsletter in my Bookshop store

He was an inspiring orator, so eloquent that his phrases have resonated through the decades to our time:

We shall go on to the end, we shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender…

He was a beloved public figure: Wherever he went, he drew crowds who gazed adoringly at him and called him “Winnie.”

He was the prime minister who sustained his people through Germany’s deadly and traumatizing aerial attacks on their island almost through sheer force of will.

Winston Churchill is the epicenter of Erik Larson’s 2020 book “The Splendid and the Vile,” a riveting examination of Churchill’s first year as prime minister, when Germany took World War II to the skies, bombing London and other English cities in a pitiless campaign now known as the Blitz. Churchill’s first day as prime minister in May 1940 was marked by Germany’s invasion of Holland and Belgium. By the time he reached his first anniversary, the Blitz had killed 45,000 fellow Britons and injured countless more. There were the indirect casualties, too; Larson ascribes author Virginia Woolf’s March 1941 suicide in part to her anguish over the loss of two beloved homes to the Blitz.

“The Splendid and the Vile” rests atop a pile of research. Larson excavates details, quotes and scenes from documents ranging from official records to diaries kept by Churchill’s daughter Mary (17 at the time) and others close to him. In a Smithsonian interview, Larson described how he approached what could have been an overwhelming task:

I scoured various archives in hopes of finding fresh material using essentially a new lens. How did he go about day to day enduring this onslaught from Germany in that first year as prime minister?

Larson places Churchill’s leadership in context by painting a broad picture of English life under siege. The German Air Force drops not only bombs but also flares that spark lethal fires, sometimes in the very air raid shelters where people have sought refuge. The rich move into hotels with reinforced walls and take their nightclubs underground. Everyone else hustles to do as much as possible during the day because the country must stay as dark as possible after sunset to minimize targets for German bombers (it becomes common for nighttime pedestrians or drivers to accidentally ram themselves against objects they didn’t see). With death raining from the sky and a very real threat of invasion from the sea, people cast aside longtime propriety in favor of immediate pleasure. Churchill’s staff discovers to their horror one day that landscaping work at his countryside retreat, Chequers, has unintentionally turned the drive into a giant arrow pointing to the house for anyone looking down from above. Churchill himself goes up to the roof to watch the bombardments; in between, he assiduously courts President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his representatives, doing his best to lure the skittish Americans into an alliance.

Meanwhile, Nazi Deputy Fuhrer Rudolf Hess gets it into his head that he needs to broker a settlement with Britain before his boss, Adolf Hitler, invades Russia and commits Germany to fighting on a second front; Larson’s telling of that story renders it almost comical.

I’ve thoroughly enjoyed the other Larson books I’ve read. And as a movie and TV buff, I was delighted by two recent portrayals of Churchill: Gary Oldman’s Oscar-winning turn in the 2017 movie “The Darkest Hour” and John Lithgow’s Emmy-winning depiction in the Netflix series “The Crown.” So when “The Splendid and the Vile” came into our household, courtesy of my mother-in-law, of course I was going to read it. It’s a splendid narrative about a vile year.

One of my closest friends was one of the children evacuated to the US because of the blitz. She did not see her parents again for four years. And I'm reminded by this beautifully written summary off The Splendid and the Vile that the Sadler's Wells Ballet, now the Royal Ballet, kept on dancing as the bombs fell, in defiance of the enemy they called Jerry. Not sure Larson is right about Virginia Woolf, many factors caused her suicide. I think I need to read this book.