'The Chinese Question': History

Mae Ngai's Bancroft Prize-winning book weaves numerous threads of Chinese and Chinese American history into the contextual tapestry we didn't know we were missing.

This post contains an affiliate link or links. If you use a link to buy a book, I may earn a small commission. You can find all the books that have been featured in this newsletter in my Bookshop store.

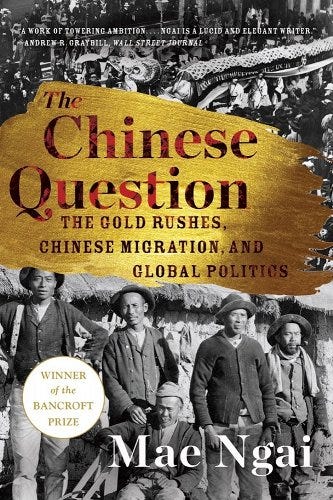

A couple of months ago, a friend offered me an extra ticket to a lecture by Columbia University historian Mae Ngai, who was going to talk about her latest book, “The Chinese Question: The Gold Rushes, Chinese Migration, and Global Politics.” I wasn’t familiar with Ngai’s work, but the topic sounded interesting, so I accepted.

Ngai was formal and somewhat stiff behind the lectern, mostly reading from written notes, which were a tad dry. But after her lecture, when the host invited her to join him in a small seating area and brought out a third person for the conversation, she relaxed and turned out to have an engaging personality and a wry sense of humor. Afterward, I bought a copy of her book, whose cover design heralded “The Chinese Question” as a Bancroft Prize winner; Ngai had said winning the Bancroft meant quite a bit to her, as it’s awarded by a jury of peers. The book is indeed a tour de force of research and writing that connects long-isolated aspects of Chinese and Chinese American history.

The question at the heart of the book is, to put it bluntly and in a probably oversimplified way, how Western countries should respond to Chinese immigration. Ngai’s research took her across the United States and to Australia and South Africa — three countries where gold rushes drew Chinese workers en masse, setting them on a collision course with white governments and residents. For the book’s epigraph, Ngai chose another question, a quote from Toni Morrison: “What is the matter with foreignness?”

Ngai, who is Chinese American, said in her lecture and foreword that the book grew out of an interaction she had with a student wrongly convinced that Chinese workers in 19th-century California were indentured workers, often derisively called “coolies.” Her response: “I vowed I would slay the coolie myth.”

Growing up, I often felt as if people of Chinese descent attracted a specific flavor of vitriol. It combined white supremacy with exclusion: not only were we considered inferior, but we were also assumed to be foreigners who shouldn’t be here. While other Asian kids also were told to “go home” or “go back where you belong,” China was typically the only country that was invoked specifically.

I figured that was because China was the best known Asian country and the source of the most immigrants. Ngai’s book adds another consideration: that in these three countries with a common Anglo heritage, “anticoolieism was foundational to identities of class, nation, and empire.” So much so that it became a permanent part of the collective consciousness.

The Chinese question played out differently in each country, and Ngai examines how in detail. The U.S. codified exclusion for decades. Australia used a variation on exclusion in an attempt to segregate Chinese immigrants in certain parts of the country. South Africa recruited indentured workers from China with the intent of using them as minimally paid muscle.

In looking at each situation, Ngai not so subtly rejects a prevailing depiction of the Chinese as passive victims oblivious to their rights. Take South Africa: I learned about a Chinese ambassador named Zhang Deyi who spent three months negotiating fair employment terms for Chinese workers there. I learned that the workers themselves joined with Gandhi in a passive resistance campaign to protest their treatment. Meanwhile, residents of China responded to the U.S. exclusion act with a months-long boycott of American goods, something I’d never heard about.

Ngai contends that the very premise of the “Chinese question” — “who could belong, who was worthy of rights, who could be a citizen” — gave rise to what she calls a global race theory.

In the United States and the British settler colonies, the Chinese Question pushed against established principles of equality to marginalize China within the family of nations and to cast Chinese people as racial inferiors within the family of humankind.

My mother majored in Chinese history in college and later taught it before moving to the United States. She admonished me frequently as a child to be proud of my roots, distant as they might be, in a 5,000-year-old civilization. Meanwhile, at school, I was being taunted with racist slurs and informed of my supposed inferiority. The cognitive dissonance was, and still is, jarring.

Ngai’s scholarship paves the way for a fuller understanding of what lies behind that dissonance. It’s truly empowering.

Thank you. Going to add to TBR list. I appreciate that you review books other than those on best seller lists.

The review, not what happened to you in school, not to mention on a minor level before my eyes a couple of years ago when we both participated in a public event.