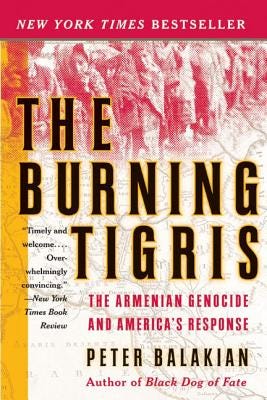

'The Burning Tigris': The story of the Armenian genocide

Peter Balakian's 2003 history goes into heartbreaking detail about a horrific era that launched America's first international human rights movement.

This post contains an affiliate link or links. If you use a link to buy a book, I may earn a small commission. You can find all the books that have been featured in this newsletter in my Bookshop store.

I can still see the look of incredulity on my friend’s face. He’d just told me that his family had its roots in Armenia. When I admitted my ignorance of the country’s history, he said, “You’ve never heard of the Armenian genocide?”

I’ve been meaning to address that gap ever since. So when I reached Armenia in my tour of global literature, I decided it was time.

Peter Balakian, an Armenian American scholar, author and poet, shrewdly opens “The Burning Tigris,” his detailed, heartbreaking 2003 history of the genocide by framing it from an American perspective, giving us a direct connection to what otherwise might seem a distant disaster. For Americans, he writes, the massacres of Armenians inspired the first international human rights movement in our history.

This movement would help define American ideas about international human rights and responsibilities, and over the next four decades it would permeate American culture. Intellectuals, politicians, businessmen, churches, civic organizations, and schoolchildren who sold ice cream and lemonade to raise money, would all work in various ways to help save the Armenians from slaughter at the hands of the Turks.

Then, after World War I, the international power dynamics shifted as America entered the automobile era and developed a thirst for oil — oil that could be acquired in Turkey.

The Armenian genocide that began in 1915 was presaged by a series of massacres from 1894 to 1896. The American response to the massacres drew in such noted figures as Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross; her mission to Armenia “anticipated the kind of work the Peace Corps would do in the second half of the twentieth century,” Balakian writes. The response also drew in everyday volunteers from coast to coast who raised funds in staggering numbers. At the end of a yearlong drive, “Americans had raised more than three hundred thousand dollars in an age when a loaf of bread cost a nickel.”

But money could not restore the losses, which were measured not only in lives but also in the devastation of Armenian society and culture. Entire towns and villages were emptied, churches and monasteries were destroyed, and survivors were forced to convert from Christianity to Islam on pain of death.

A couple of decades of an uneasy peace followed. But World War I put Turkey on a footing that boded ill for the Armenians.

In short it created an armed and mobilized society, a heightened sense of national security crisis, a deepened xenophobia, and the sense of chaos that accompanies war. … All these conditions were used to mobilize the ‘final solution’ for the Armenians.

Balakian uses the phrase “final solution” quite deliberately, noting parallels between the Nazi Party and Turkey’s Committee of Union and Progress. Both were skilled at using the “bureaucracy of the state” to commit mass murder; both profited from their victims, looting bodies and homes and towns.

One notable difference was that an effort to hold war crimes trials in Turkey fell apart, ending with the release of 43 Turks accused of perpetrating the massacres. “The abandonment of the Constantinople war trials was a major failure,” Balakian writes, “and it helped to accelerate the amnesia in the West about the Armenian Genocide in the ensuing decades.”

Years after visiting the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, I still think of the shoes once worn by the Nazis’ prisoners, the sheer mass of the collection unfathomable. And I have no doubt that years after reading Balakian’s book, I’ll still think of the bones he describes as strewn for miles, their sheer numbers unfathomable. It’s estimated that 1.5 million Armenians died in the genocide, out of a population of about 2 million.

Balakian writes that Turkey doesn’t want the world to think of the Armenian genocide at all, has in fact spent decades working to erase its memory. His book speaks passionately for all those silenced, gives them back their voices.

thanks for the clarification Amy.

I confess I'm really surprised that the Armenian genocide is new to you, but it's new to my son in law as well, although not my daughter. That's because her father, historian Franklin C. West, 30 years or so ago, co taught a course on genocide at PSU with American historian Tom Morris, and an Armenian professor of English (I think it was Greg Gosian)--Morris taught about the genocide of First People. And my generation knew about the Armenian genocide the way your generation knows about Viet Nam, etc. This looks like a really interesting book and I'll put it on my list, thank you a'am.