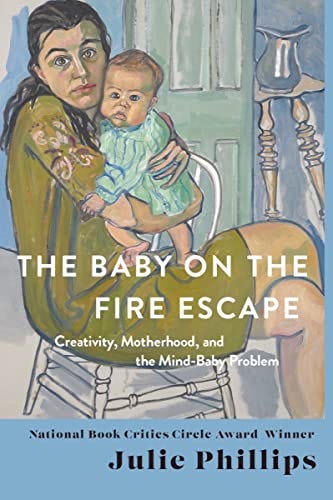

The Baby on the Fire Escape: Nonfiction/women's studies

What does the Venn diagram of motherhood and creativity look like?

I’ve long admired and enjoyed Ursula K. Le Guin’s vast body of work, and that led me to this new book by Le Guin’s official biographer, Julie Phillips, about the intersection of motherhood and creativity. Le Guin is the subject of a chapter in “The Baby on the Fire Escape,” which explores how she and other notable authors — Alice Walker, Audre Lorde, Doris Lessing, Susan Sontag — tackled what Phillips calls the “mind-baby problem.”

***

A few years ago, I decided to attempt NaNoWriMo, as National Novel Writing Month is known to aficionados, mostly to see if I could actually write 50,000 words in thirty days. Now I am the proud owner of a NaNoWriMo “winner” T-shirt (which I paid for) and a sandpaper-rough draft of a young adult novel that sits covered in electronic dust in the depths of my Google Drive. After a short break I tried revising my “novel,” but never finished because (a) I couldn’t stop revising the same chapters over and over (b) I inadvertently put my literary baby in a corner and couldn’t figure out how to pull her back out (c) I was feeling increasingly guilty about ignoring my flesh-and-blood sons in favor of my made-up daughter.

***

How, Julie Phillips wondered, do authors and artists who are also mothers carve out the time and reserve the energy needed for their vocations? She writes in the opening pages of “The Baby on the Fire Escape”:

The frustration — and pleasure — that writer-mothers experience seems better expressed with images of improvisation and compromise than of multiple selves in amicable concord. … This is the baby on the fire escape — not the slanderous story [claiming artist Alice Neel once put her baby out on her apartment’s fire escape so she could finish a painting] but the reality that it stands for, the precarious situation in which the child is just far enough out of sight and mind for the mother to have a talk with her muse.

To illustrate this reality, Phillips explores how women such as Alice Walker, Audre Lorde, Doris Lessing and Susan Sontag constructed it for themselves. Phillips observes that second-wave feminists yearned for a gender equality that would “resolve all the practical and emotional contradictions of writing and mothering.”

In this narrative, the problem is interruption (whether by children, guilt, or self-doubt) and the resolution is harmony. But as I look at mothers’ lives, I think these visions may not do justice to the actual maternal creative process, which alongside periods of harmony seems to involve foregrounding disruptions, leaping across gaps, piecing together careers, and other provisional and drastic measures.

***

I tried NaNoWriMo again a couple years later, but this time quit well short of Nov. 30, with only a brief pang of regret. Forcing myself to produce a set minimum of words each day just didn’t align with how I write, which is in spurts. This was also true during the quarter-century I spent as a journalist. On some days the words came easily; on others, I read and re-read notes to little avail. Last fall I was invited to write an editorial. I made a few false starts, let the topic bobble in my subconscious for several days, and then suddenly found myself on the couch at 2 a.m., writing and rewriting with pen and paper to avoid disturbing my family. Inspiration strikes when it strikes. If I had had a fire escape when the children were small, I don’t know that I wouldn’t have thought about putting the baby out there at a moment of creative white heat.

***

Some of the chapters in “The Baby on the Fire Escape” narrate the life of one woman; others gather vignettes about several women under a theme, such as “Art Monsters and Maintenance Work.” That particular chapter includes a nod to New York artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who, Phillips writes, “linked maternal labor to other undercompensated forms of maintenance work” through performances such as washing a museum gallery’s floor. In Ukeles’ telling of the story of her inspiration, she had a child, she became a maintenance worker, and she needed to connect those two selves somehow.

In a subsequent chapter on Doris Lessing, Phillips quotes from a letter in which Lessing told a friend that the trouble with motherhood “is not the work itself but the conditions under which it is done.” The same remark could be made about writing or another creative pursuit. Alice Walker’s writing was for her an act of resistance and healing, but motherhood would keep interrupting. Audre Lorde’s writing proved challenging for the literary establishment to grasp — “she would have to create through her work the audience she needed,” Phillips writes. They were far from alone, as “The Baby on the Fire Escape” shows, in having to constantly readjust, reconsider, renegotiate and revise the ways in which they reconciled their mother and artist selves. Le Guin’s story is one of the few predominantly positive ones, and that was because she found herself a unicorn in a husband who respected and supported both her mother and writer selves.

In an online chat hosted this week by Hedgebrook, a women’s writing community in the Pacific Northwest, Phillips (a Hedgebrook alumna) called self a key theme of “The Baby on the Fire Escape,” as in “I want to have enough of myself back in order to get the work done.” Her book posits two essential ingredients of a woman’s creativity and artistry as self and time: holding to the notion that she has the right to set boundaries and to “the conviction that she has the right to make her art.”

A word about Juneteenth

Black authors have been part of America’s history since Phillis Wheatley published her first poem in 1767, at age 13. Their work played a critical role in my adolescence — in an era when published Asian American authors were very few and far between, I found common ground with African American authors writing about racism, discrimination, marginalization and erasure.

So this Juneteenth weekend, I’d like to propose three literary ways to celebrate the holiday:

Read a book about Black American history. I’ll be reading “On Juneteenth,” by Pulitzer Prize-winning Harvard historian Annette Gordon-Reed.

Support a Black-owned bookstore. I bought my copy of “On Juneteenth” at Portland’s Third Eye Books. Oprah Daily has a list of 127 Black-owned bookstores throughout the U.S. You can also support bookstores by following their social media accounts and telling friends and family about them.

Support Black authors. If you’re in the Portland area, you can attend the Freadom Festival, a celebration of Black authors and readers, from noon to 6 p.m. today. Ask your local library to carry titles by Black authors and attend readings by Black authors when you can.