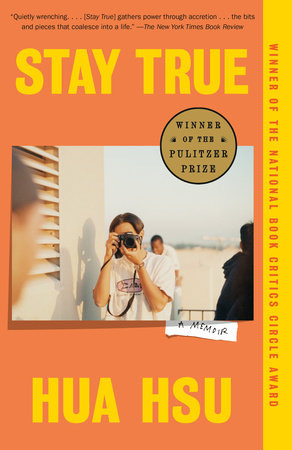

'Stay True': A meditation on friendship

Hua Hsu's memoir centers on a college friend who had an immeasurable impact.

This post contains an affiliate link or links. If you use a link to buy a book, I may earn a small commission. You can find all the books that have been featured in this newsletter in my Bookshop store.

At first I thought “Stay True,” New Yorker writer Hua Hsu’s Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir, was going to be about his father and him. This was based on an excerpt I read somewhere, maybe in The New Yorker itself. The excerpt focused on a young Hsu’s relationship-by-fax with his dad whenever the father was working in Taiwan, which he did for lengthy periods. This wasn’t a parental separation situation disguised as a career opportunity for Dad. It was just that Hsu’s father kept up both his lives, his original one in Taiwan and his new one in the U.S. I could relate. My dad had done something similar, though without the faxes.

But it turns out this excerpt is really part of the backstory, offering a glimpse of some of the baggage Hsu is toting as he arrives at college, at Berkeley, wary of anyone exuding poise and contentment.

Like Ken.

Hsu’s worldview has been shaped by being a child of recent immigrants. He’s inclined to “feel discomfort at a molecular level, especially when doing typical things, like going to the pizza parlor on a Friday night, playacting as Americans.” Ken is from that slice of Japanese American society that’s been American for multiple generations: “Some of them had never even been to Japan, and some, too, had family who fought against Japan in World War II.”

They develop a friendship, and not just any friendship — the kind of intense friendship in which anything is fair game for an all-night conversation and everything feels consequential. Looking back, Hua seems amazed that Ken agreed to become his friend. Which makes the loss of that friendship all the more devastating.

There are many currencies to friendship. We may be drawn to someone who makes us feel bright and hopeful, someone who can always make us laugh. Perhaps there are friendships that are instrumental, where the lure is concrete and the appeal is what they can do for us. There are friends we talk to only about serious things, others who only make sense in the blitzed merriment of deep night. Some friends complete us, while others complicate us.

And sometimes all these currents flow through a single friendship. Hsu recounts moments when Ken made him feel hopeful, made him crack up. He found Ken useful for burnishing his own social standing. He and Ken pondered serious topics like social justice and got silly partying until the wee hours. Ken was a sidekick, a burr.

A quarter-century later, Hsu still feels a Ken-shaped hole in his life. “There’s a way I took this friendship for granted,” he said in an interview with BookPage. “ … The question of closeness only becomes visible when it’s no longer there.”

This also resonated with me Amy, perhaps because of the beauty of his prose. I believe I read much of it in the New Yorker. And I'll add that writing about male friendship is rare, other than memoirs of shootin' and fishin' with the guys, and I learned a thing or two from reading this memoir.