I’d been expecting the news for a while, given David McCullough’s age. But when my brother texted me the news of the Pulitzer Prize- and National Book Award-winning author and historian’s death, it was still quite saddening. Here’s a tribute to the man I was fortunate to see in a special way.

The course description was just different enough to catch my eye: American history taught with an emphasis on influential figures, by a historian whose name I didn’t recognize but who’d apparently had a PBS show. I’d grown up watching PBS, which my parents venerated. So I registered for the course.

We didn’t have cell phones or the internet back then. Still, by the time David McCullough strode onstage to give his third lecture as a visiting professor at Cornell University, his course had gone viral: The auditorium in Goldwin Smith Hall was packed past capacity. Students filled every seat, stood against the entire length of the back wall, even sat in the aisles. McCullough smiled, his shock of white hair gleaming under the lights and his bright blue eyes warm, then politely but firmly said that anyone not officially enrolled in his course would have to leave. He didn’t want to get in trouble with the fire marshal, he joked.

As the extras silently filed out, the rest of us looked around. I caught the eye of a student I didn’t know and we exchanged triumphant grins. Around us, others were doing the same. Then we all settled back for a semester that remains the most memorable course I took in four years of college.

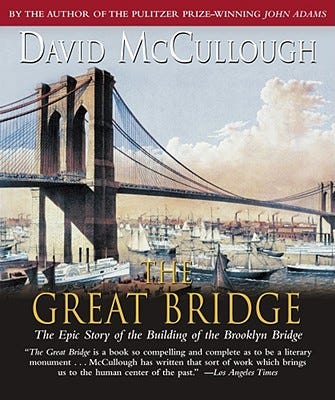

There were the books. I’d never read history books like the ones McCullough had us read. My first thought when I looked at the syllabus was that he had a pretty high opinion of himself, because the reading list included several of his own books. Then I actually read “The Great Bridge,” which brought to vivid life those who created the Brooklyn Bridge, from concept through construction, and “The Path Between the Seas,” which did the same for the Panama Canal. Better yet, the books wove in illuminating political and social context for these vast undertakings. And they read like novels.

When we weren’t reading McCullough’s books, we were reading books we probably wouldn’t have picked up otherwise. I no longer have the syllabus, much to my regret, so I don’t remember specific titles or authors. But there was a biography of Lena Horne, which he told us he wanted us to read because it opened a window onto America’s seldom acknowledged Black bourgeoisie. There was a book about life in Appalachia, a similarly overlooked region. There was a book about a man who wasn’t a household name but who’d been a highly influential force through multiple presidential administrations.

Then there were the lectures. One morning we came in to find the auditorium dark and a slide projector glowing. McCullough announced that his lecture that day would be about American art, then took us on a tour of John Singer Sargent, Thomas Eames, Mary Cassatt and others, explaining how their works reflected their times. Another morning we were told to meet in nearby Sage Chapel, which had a performance stage. There McCullough and a friend who was a professional pianist held a lively discussion about American composers, and then the friend played George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” to a completely attentive and awed audience.

And then there was the term paper. McCullough told us he didn’t do quizzes or tests. He just wanted us to research and write a really good paper. One day he had his teaching assistants hand out historical photos with short captions attached; we were to use the photo we got as a prompt for coming up with a topic, which our TA would approve for relevance and rigor. Another student asked our TA if he’d ever seen a term paper assignment like McCullough’s. The TA raised his eyebrows and said he’d never seen a course like McCullough’s.

I was working for the English Department that year as an on-demand writing tutor — several times a week, I’d station myself in a campus computer lab, available to anyone who needed help with their writing. One night a student came to the tutor table with a draft of a history paper. He explained that it was a rather odd assignment — he’d been given a photo from something called a newsreel and while figuring out what a newsreel was, he’d become fascinated by the medium and decided to write his paper on newsreels themselves.

I asked if he was taking McCullough’s course. His eyes lit up, and for a few moments we gushed about how much we were both enjoying it. He asked what I was writing my paper on. I said I’d gotten a photo of a woman at the Ellis Island immigration center, decided I wasn’t going to break any new ground on that topic, and turned instead to researching and writing about Angel Island, a lesser-known facility off the coast of northern California that I’d recently learned about in an Asian American studies course. I’d never been so engaged in a history paper.

McCullough’s final lecture came all too soon. We listened raptly, taking notes to the end. When he was done, we gave him a standing ovation. He smiled, seemed to tear up a little, thanked us and left the stage. Then, spontaneously, a line formed, a line of students wanting to shake McCullough’s hand and speak to him. I joined it.

In the next few minutes, my mind turned over multiple sentences, trying to craft one that would impress McCullough and bring home to him how much I’d appreciated his course, a standout comment that he’d remember whenever he thought back on his time at Cornell. But when I finally stood in front of him and he looked at me and smiled, I merely grasped the hand he held out and said, “Thank you.” It was all that really needed to be said, after all.

Thank you, David McCullough. Rest in peace.

Thanks for sharing this Amy! I’ve loved McCullough’s books for a long time. I had a similarly excellent experience at Rutgers many years ago when Gloria Steinem was our instructor for a Women’s Studies class I was in… when word got out, it was standing-room only. We have so much to learn from the giants.

This is really lovely Amy, how very lucky you were. The first book by McCullough that I read, long after I was a college student, was Mornings on Horseback, recommended by our pediatrician for the description of Teddy Roosevelt's asthma treatments, pre-modern pharmacology. Thank you for this memoir and tribute.