How We Do Family: Pride Month

One couple's journey from accidental parenthood to trans pregnancy.

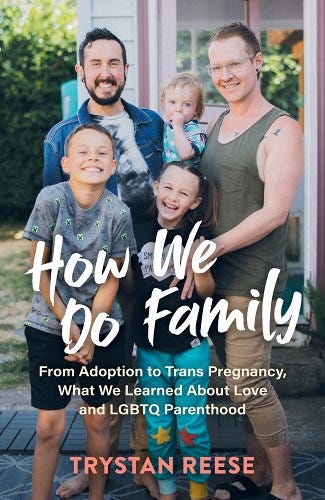

In my previous life as the books wrangler for The Oregonian/OregonLive, books continually showed up unsolicited in my mailbox. Among those that arrived in 2021 was “How We Do Family: From Adoption to Trans Pregnancy, What We Learned about Love and LGBTQ Parenthood.” The author lived in Portland and had been the subject of coverage in The Oregonian/OregonLive, so I put the book in my to-read box.

It stayed there for a long time, as other books kept claiming my attention. Still, I never moved it to the giveaway box. This month, in a nod to Pride Month, I finally opened it to skim the first chapter. Before I knew it, I’d read the first 92 pages.

***

Trystan Reese is an educator, facilitator and storyteller, and “How We Do Family” is accordingly infused with empathy, openness and, most of all, compassion. He’s open in sharing his story, even the parts that must have been difficult to write about. He’s open about what his two older children went through before they finally settled in a compassionate home where they could start healing. He meets the reader with open compassion for wherever they might be when it comes to, say, understanding trans language or supporting trans rights.

As Reese guides the reader through his family’s story, from meeting his partner to finding himself co-parenting his partner’s nephew and niece to deciding to have a baby, he ends each chapter with advice gleaned from experience that’s both specific and universal. Takeaways are also sprinkled throughout the chapters. During a squabble between the older children, Reese goes into facilitator mode, modeling how to help defuse tension and find a solution that works for everyone. But he’s never preachy, only encouraging and engaging as he shows how he found his way through each challenge.

The book does have a bit of a “They’re Just Like Us!” air about it (“Transgender People — They Make Pancakes for the Kids! They Worry About the Rent!”). But a little intentional relatability is rarely a bad thing, especially for people who are frequently misunderstood, marginalized and maligned.

***

Growing up, when we drove at night through residential areas, I loved to look at the lit-up windows and imagine the lives of the people inside. When it came to people I knew, I was especially interested in kids who had families markedly different from mine. N. was the only child of a divorced mom. A., who was Vietnamese, had been adopted by two white parents who had also adopted two Black boys. J. had a white mother who used a wheelchair and a Black father who was blind. As far as I could tell, these kids were as loved and cared-for as I was. I learned from them that families didn’t have to conform to any one mold for kids to flourish.

***

A dispatch from the Department of From the Mouths of Babes:

Reese and his partner, Biff Chaplow, are in court to finalize their adoption of Chaplow’s nephew and niece. “I was completely convinced that something would happen to ruin the day,” Reese writes.

The judge looked over her glasses at us and said, “Well, what do we have here?”

Too young to understand courtroom decorum, five-year-old Hailey declared, “It’s our love family!”

The ceremony proceeds without a hitch. The kids get teddy bears. Everyone cries happy tears.

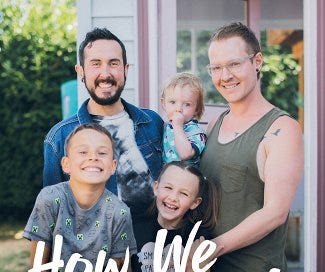

Some pages later, a selection of photos appears. In the next to last one, Reese and Chaplow are smiling; in the last one, they have more serious expressions. The kids go from small and guileless to less small and posed. But both in photos, one thing remains the same: This is clearly a family.

***

A word about abortion access

It didn’t matter that I knew to expect Friday’s Supreme Court Dobbs v. Jackson opinion overturning the constitutional right to abortion that we had for a half-century. The ruling still felt like a punch to the stomach.

Some have cited Margaret Atwood’s 1985 dystopian novel “The Handmaid’s Tale,” in which a rigid theocracy reduces women to breeding vessels, as a warning that we should have heeded more closely. Atwood has said, though, that she long considered her book to be “far-fetched” fiction.

More chilling to me, partly because of its publication during the Trump Administration, was Leni Zumas’ 2018 novel “Red Clocks,” whose characters inhabited an America where abortion had been recriminalized. She told me in an interview: "There's not much in 'Red Clocks' that hasn't been suggested by an actual U.S. lawmaker.”