'Dancing in the Mosque': A memoir from Afghanistan

What it was like to come of age under the Taliban.

This post contains an affiliate link or links. If you use a link to buy a book, I may earn a small commission. You can find all the books that have been featured in this newsletter in my Bookshop store.

I keep annual logs of the books I finish. Nothing fancy — just lists of titles and authors. In reviewing those lists recently, I noticed a glaring omission: books by authors outside the United States. So in 2023, I’m reading at least one book a month by an author from another country. To keep things simple, I’m going through the countries alphabetically.

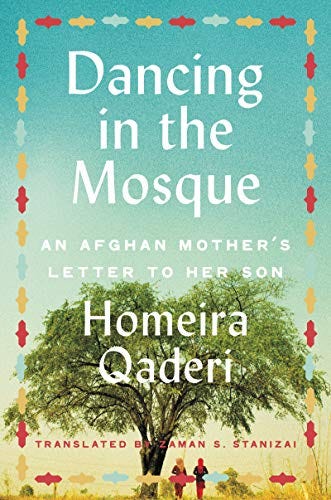

First up: Afghanistan. After a little digital digging, I found Homeira Qaderi’s “Dancing in the Mosque: An Afghan Mother’s Letter to Her Son” at my library. Qaderi now lives in the United States, where she pursues a career as a writer, activist and educator. This would not be an unusual sentence to write about an American woman. But for Qaderi, it is a sentence that encapsulates years of struggle and fear.

Qaderi writes evocatively and fondly of her childhood, spent in the close embrace of her grandparents, parents, siblings and neighbors. In those years, no one thought anything of girls going to school or roaming freely. Her best friend was a neighbor boy, with whom she played daily.

The rise of the Taliban was at first a mere flicker in her consciousness. Qaderi’s home was in western Afghanistan, far from the eastern capital of Kabul. Even when Kabul fell, the news seemed distant, a concern for others.

Then the Taliban arrived. Qaderi’s father buried his beloved books. Qaderi had to don a burqa and persuade one of her brothers to escort her anytime she left their home. Not for school — that was over. But Qaderi couldn’t let go of the idea of education. She started a secret school, giving it a religious facade by holding it inside a tent being used for a mosque. When Taliban soldiers’ footsteps sounded outside, the children knew to swiftly tuck their notebooks and pencils inside their clothes.

One of the men who regularly patrolled outside the mosque became suspicious of her. But another, younger soldier came to her defense and joined in her subterfuge — because he, too, wanted to learn to read and write.

We’ve all seen the headlines and photos from Afghanistan for decades now. Qaderi’s memoir — interlaced with sorrowful letters to the son she was forced to leave behind — accomplishes the much-needed feat of imposing a human face over the drumbeat of dispatches it’s become too easy to turn away from.

As I was reading “Dancing in the Mosque,” I became curious about the dishes Qaderi mentioned. Sharing a meal is, of course, one of the oldest forms of getting to know another person. Turns out an Afghan food cart operates about a 20-minute drive from my home. So one recent weekend, I packed my teen and his girlfriend in the car, promising a free lunch, and headed there. We found the cart tucked among other carts selling a range of other cuisines: Mexican, Cuban, hot dogs, Thai, sushi, barbecue. While the kids ordered at the Filipino cart, I asked one of the women in the Afghan cart for mantoo (beef dumplings), boolani dogh (stuffed flatbread) and dogh (a yogurt drink). She raised an eyebrow at the last item. “Sour,” she warned. “That’s OK,” I said.

She was right to be dubious. To my palate, the dogh, heavy on yogurt and cucumber, tasted like drinking a salad dressing. I got halfway through and saved the rest for my husband to try. But the mantoo, topped with lentils and a yogurt sauce, were delicious. And the crisply fried boolani dogh, filled with potatoes, was a revelation — the kids liked it, too.

As I ate, I wondered about the woman who’d just sold me lunch. She had a heavy accent that made me think she was an immigrant — had she gotten out before Taliban rule? Before reading “Dancing in the Mosque,” I would have seen her as just another food cart worker. Now I thought of Qaderi’s story, and wished I could know this woman’s, too. Such are the connections a book can make.