Bookworm: December 2024

'The Christmas Appeal,' 'The Ruined House,' 'God's Country,' 'Euphoria,' 'Fledgling'

This post contains an affiliate link or links. If you use a link to buy a book, I may earn a small commission. You can find all the books that have been featured in this newsletter in my Bookshop store.

Hope you had a wonderful holiday season. I took a 12-day break (weekends and Christmas holiday included) from work, and the time off was especially relaxing because I didn’t go anywhere near an airport, train station or bus station. Instead, I used a good portion of that time off to read. One of my best vacations ever.

Table of contents

Cozy mystery: “The Christmas Appeal,” by Janice Hallett

Religious fiction: “The Ruined House,” by Ruby Namdar

Western fiction: “God’s Country,” by Percival Everett

Historical fiction: “Euphoria,” by Lily King

Science fiction: “Fledgling,” by Octavia Butler

“The Christmas Appeal”

“The Christmas Appeal” is a delightful tale of an English community theater troupe feverishly preparing for and putting on its annual pantomime, a quirky Christmas tradition that even the royal family enjoyed. Backstage politics have the Fairway Players already on edge by the time the curtain rises: The couple that once co-chaired the troupe has been voted out but remains highly involved, and the new co-chairs are determined to put on a “real” show, not some superficial farce. Naturally, what ensues onstage, and continues to ensue behind the scenes, is pure farce.

Better yet, author Janice Hallett has given us an epistolary novella. She makes excellent use of emails, texts, WhatsApp messages and police interview transcripts to tell the story. And as a novella, this was the ideal length for a busy holiday season.

I’ve always thought the ability to craft dialogue that develops characters is the mark of a strong writer, and Hallett certainly possesses that ability, having essentially written an entire book in dialogue. Take the collection of emails that opens “The Christmas Appeal.” When Celia Halliday sends her annual Christmas email on Dec. 1, her ode inflating her amazing family and their amazing accomplishments is promptly punctured by two responses: one to Celia that is the polar opposite in tone and content, and another about Celia’s email that snidely and hilariously annotates all of its boasts. By the end of these three emails, I had a good sense of the kinds of people the writers were, and we were off.

Holiday cheer indeed. Put this novella on your list for next year’s gift-giving.

“The Ruined House”

I wanted to read a Hanukkah novel. My first search turned up several romances, but I wasn’t in the mood for a romance. My second search turned up “The Ruined House,” by Ruby Namdar, translated from Hebrew by Hillel Halkin.

This book, which won Israel’s top literary award, the Sapir Prize, was one of five on a “Best Books for Hanukkah” list put together by novelist and comparative literature scholar Dara Horn. Asked how the book ties back to Hanukkah, Horn replied:

The Ruined House takes you back to the ancient temple that Hanukkah celebrates reclaiming. And it powerfully makes the point that we’re all connected to the history that haunts us.

Namdar’s protagonist is Andrew Cohen, a 52-year-old New York University professor of cultural studies who seems to have it all: tenure, a divorce amicable enough that he and his ex-wife still share Thanksgiving dinners and a summer house, two daughters he remains close to, a 26-year-old girlfriend who laughingly introduces herself to his boss as his “midlife crisis,” a gorgeous apartment, invitations to all the hottest cultural events in town. He’s eagerly anticipating a big promotion that will gild his academic legacy. And oh yes, he’s Jewish, but not enough to sit through a full Yom Kippur service. The life he leads is fully secular and defined by material appetites.

Then, over the course of the year leading up to the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, his life collapses. He starts having visions of ancient rites and the Temple of Jerusalem. He has dreams and nightmares that tumble his past and present together, often horrifyingly so. When he takes a train trip, he finds himself the captive audience of a fellow passenger who will. not. stop. narrating a Holocaust trauma he believes he experienced in a past life.

Amid the elegantly wrought narrative, Namdar weaves in Talmudic-style pages that tell a parallel story about a young priest living millennia earlier. (“Cohen” means “priest.”) In an essay titled “The Drama of the Talmudic Page,” published when his novel came out in 2017, Namdar wrote:

I find the drama of the Talmudic page so inspiring, so captivating, that I felt compelled to “import” it into my own work. The subplot of my new novel, The Ruined House, is not only told as a Talmudic tale but is also laid out on the page as one. Parts of the text are my own fiction, while others are original quotes from different parts of the Talmud and of various other midrashic and kabbalistic sources.

“The Ruined House” was an unexpected reading experience, and I enjoyed it.

“God’s Country”

In this Western, Percival Everett, the author and USC professor best known these days for his National Book Award-winning novel “James,” has taken all the tropes of the genre, packed them onto a mule and sent it braying down a satirical switchback.

Our guide atop this mule is a white man named Curt Marder, whom we meet in 1871 as he arrives home to find his house on fire and his wife in the hands of the arsonists. Foreshadowing “James,” Everett’s narration is Twain-esque:

She was swearin’ a blue streak that made me proud, dang proud. I couldn’t rightly make out the words, but the tone was right for good cussin’.

Alas for Sadie Marder, her man is all about tone, not action.

It’s not like I didn’t do anything. I did pull my gun out of its holster and stand my ground.

While Marder stands his ground, the miscreants ride off with his wife, his house burns to the ground and his dog dies impaled on an arrow. (Only the last crime elicits sympathy among his peers.) He vows to get his woman back, but through a series of unfortunate events, he’s left a penniless laughingstock. The sole individual who comes to his aid is a Black man named Bubba, known for his tracking talents, who agrees to search for Sadie in exchange for some of Marder’s 52 acres.

With that, we’re off on an antihero’s journey. Along the way, Everett throws into Marder and Bubba’s path just about every stock Western character: the innocent young orphan, the seen-it-all saloon owner, the shady salesman, the equally shady preacher, the working girls, the Native American warriors, the bank robbers. Even U.S. Army Col. George Armstrong Custer makes an appearance.

What they all have in common is that they all find Marder contemptible — in a reversal of racial tropes, he’s the sad-sack sidekick to the much more capable and confident Bubba. One character mishears Marder’s name as “Dirt Martin,” and “Dirt” sticks because it fits. Given opportunity after opportunity to take the high road, he spreads himself across the low road. In another author’s hands, he might gradually attain the high road by coming to see Bubba, through their common travails, as a man deserving of the same dignity he seeks for himself. In Everett’s hands, there’s none so blind as those who will not see.

“Euphoria”

The historical novel “Euphoria,” by American writer Lily King, has been hovering at the edge of my literary consciousness since it came out a decade ago. Finally, it turned up in a box of books that a friend was giving away, and I grabbed it.

“Euphoria” explores a famed love triangle involving anthropologist Margaret Mead and her second and third husbands, fellow anthropologists Reo Fortune and Gregory Bateson. Bateson was doing fieldwork in the Sepik region of Papua New Guinea in the 1930s when Mead and Fortune turned up, looking for a tribe to study. Sparks — intellectual and romantic — flew. (See a photo of the trio in this Library of Congress exhibit.)

King’s title refers to the way that her fictional Mead, renamed Nell Stone, describes her favorite part of anthropological fieldwork.

It’s that moment about two months in, when you think you’ve finally got a handle on the place. Suddenly it feels within your grasp. It’s a delusion — you’ve only been there eight weeks — and it’s followed by the complete despair of ever understanding anything. But at that moment the place feels entirely yours. It’s the briefest, purest euphoria.

Stone and the two men, whom King renames Schuyler “Fen” Fenwick and Andrew Bankson, spend the rest of the novel chasing that hit of euphoria. They each go at it differently: Fen imitates the men he’s studying, Bankson observes with the detachment of the scientist his father wanted him to be, and Stone forges individual relationships with her subjects. “If I didn’t believe they shared my humanity entirely, I wouldn’t be here,” she tells Bankson earnestly. “I’m not interested in zoology.”

But even Stone, for all her idealistic intentions, can’t avoid the conflicts and misunderstandings that arise when one culture defines another as a specimen to be studied. In the fevered climate of Papua New Guinea, tempers rise and euphoria distorts everything.

“Fledgling”

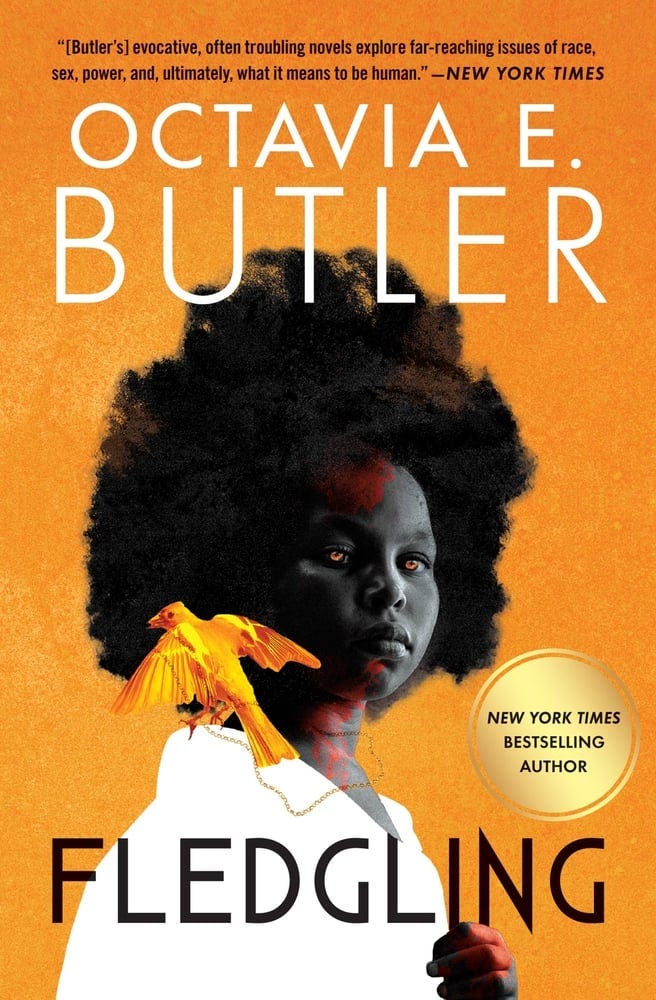

While perusing a display of science fiction and fantasy at my neighborhood library, I spotted the Octavia Butler novel “Fledgling,” which I hadn’t heard of. It was her last book, published not long before her 2006 death. A back cover blurb quoted from a Publisher’s Weekly starred review: “Butler has created a new vampire paradigm … and given a tired genre a much-needed shot in the arm.”

I’ve been having an extended vampire moment. My book club read “The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires.” My spouse and I have been watching the goofy vampire series “What We Do in the Shadows.” And in one of my favorite cultural events of 2024, we went to a Halloween Eve screening of “Dracula” accompanied by a live performance of Philip Glass’ score. So I kept the moment going with “Fledgling.”

Inside a Pacific Northwest cave, someone awakens badly hurt and unable to see, with no memory of where they are, who they are or how they were injured. They’re ravenous — when another living creature approaches and touches them, they instinctively attack, kill and eat. Later, as they heal and their vision and awareness sharpen, they realize that the victim was a human man and that he seemed to know who they were.

That would be a vampire, still a child at 53 years old, who differs from her people in two key ways: She can move about by day, provided she covers her skin so she doesn’t blister, and she looks like a small Black girl. The latter difference is the result of genetic engineering that has made her and her families a target — but in whose eyes?

“Fledgling” wraps familiar tropes in a mystery-thriller imbued with themes of race and identity. It is indeed a refreshing take on the vampire genre from a voice silenced too soon.

At the end of every year I count the number of books I finished in the past 12 months. This year’s total: 106. My top 10, in no particular order, and not counting re-reads:

“Lessons in Chemistry,” Bonnie Garmus

“Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow,” by Gabrielle Zevin

“I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes Within Us and a Grander View of Life,” by Ed Yong

“James,” by Percival Everett

“Feeding Ghosts: A Graphic Memoir,” by Tessa Hulls

“Funny Story,” by Emily Henry

“The Bonesetter’s Daughter,” by Amy Tan

“Anita de Monte Laughs Last,” by Xochitl Gonzalez

“Madwoman,” by Chelsea Bieker

“The Covenant of Water,” by Abraham Verghese

Here’s to more good reads in 2025!