Bookworm: April 2025

'Big Jim and the White Boy,' 'The Genius of Judy,' 'Honey,' 'Mysterious Creatures,' 'I'm Gonna Paint'

This post contains an affiliate link or links. If you use a link to buy a book, I may earn a small commission. You can find all the books that have been featured in this newsletter in my Bookshop store.

Table of contents

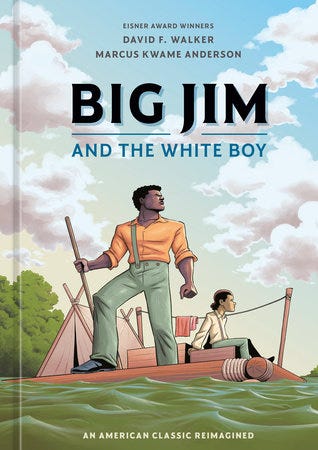

Graphic novel: “Big Jim and the White Boy,” by David F. Walker and Marcus Kwame Anderson

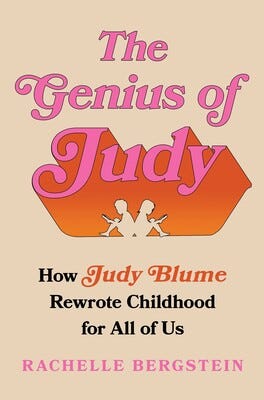

Biography/literary criticism: “The Genius of Judy,” by Rachelle Bergstein

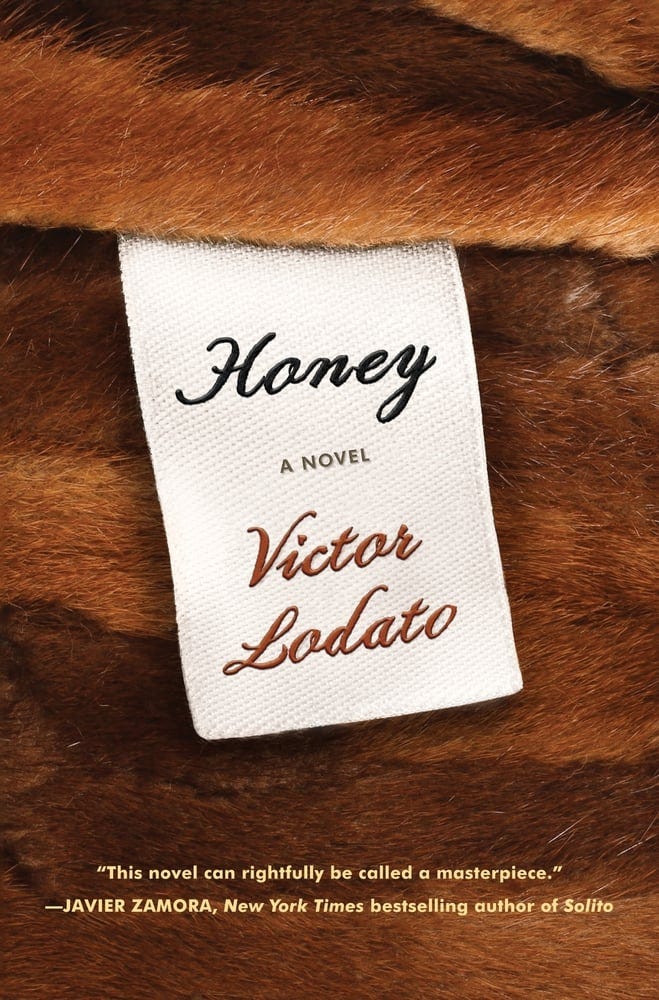

Fiction: “Honey,” by Victor Lodato

Biography/science: “Mysterious Creatures,” by Catherine McNeur

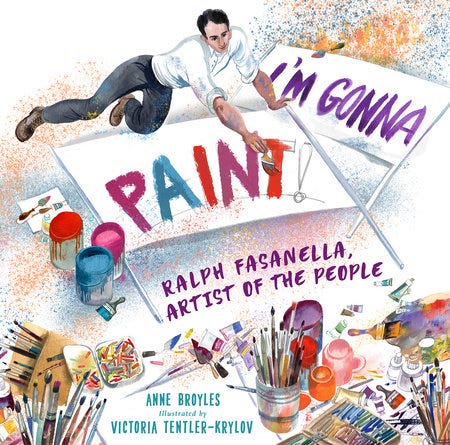

Picture book biography: “I’m Gonna Paint,” by Anne Broyles

“Big Jim and the White Boy”

Mark Twain’s Jim is having a moment.

Since Twain published “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” in 1884, Jim has become a classic literary figure. A classic problematic literary figure.

If you need a refresher: Huck is a motherless white boy on the run from the abusive father he fears is going to kill him. Jim is an enslaved Black man on the run from the white woman he fears is going to sell him. Huck and Jim have known each other all their lives, so when they bump into each other, they decide to run together.

All through their subsequent adventures, Jim remains subservient to Huck even when they’re deep in the woods far from prying eyes. Jim speaks in a thick pidgin that’s nearly impossible to decipher. Jim becomes the butt of a childish, hurtful prank that Huck finds funny because he doesn’t see his victim’s humanity. The book’s most famous moment comes when Huck literally holds Jim’s fate in his hands, in the form of a letter to Jim’s owner revealing where her lost property is.

Walker and Anderson’s take on Twain’s novel, a graphic novel titled “Big Jim and the White Boy,” reclaims Jim’s humanity, starting by placing him first in the title. In the cover illustration, Jim stands tall on a raft, grasping the rudder firmly, while Huck sits idly by. Inside, a now-elderly Jim and Huck tell their story together as a series of flashbacks to a crowd of admiring youngsters, with Jim leading the narrative while Huck uses an ear horn to keep up. Meanwhile, a young relative learns about Jim’s later life from her mother, giving him a full arc as the main character.

If the idea of retelling Twain’s tale from Jim’s perspective sounds similar to Percival Everett’s National Book Award-winning novel “James,” Walker said it’s a complete coincidence.

In an interview with Oregon Public Broadcasting, Walker said he was done writing “Big Jim” and Anderson was more than half done drawing it when their editor emailed them about Everett’s novel. "Oh, man, that was a brutal day,” Walker told interviewer Dave Miller. The two books ended up being published months apart in 2024, “James” first.

The result: We readers now have two wonderful renditions of Jim to place alongside Twain’s novel.

“The Genius of Judy: How Judy Blume Rewrote Childhood for All of Us”

This month I’m grateful to the friend who tipped me off to Rachelle Bergstein’s new book, “The Genius of Judy: How Judy Blume Rewrote Childhood for All of Us.”

“The Genius of Judy” is a biography-and-literary-criticism mashup centered on Blume’s journey from a restless housewife and mother to a much-read and oft-controversial author of 32 picture books, chapter books and middle grade, young adult and adult novels. Selected titles, such as the young adult novel “Deenie” — the target of numerous challenges and bans — are the subjects of deep dives that examine their significance in Blume’s career and the literary landscape.

Bergstein adeptly weaves together multiple threads: How Blume’s middle-class suburban childhood shaped her adulthood. How her dissatisfaction with her cosseted life tapped into, and reflected, second-wave feminism. How she shattered, again and again, the taboo against acknowledging puberty, let alone teen sexuality, in middle grade and young adult fiction. All these threads are laid down against a rich backdrop of social, historical and literary context.

Despite its title, “The Genius of Judy” is no hagiography. Bergstein offers a balanced, complex portrait of her subject as a talented, persistent, ultimately wildly successful and yet relatably fallible human being. If only all author biographies were like this.

“Honey”

In keeping with my motto of “buy and support local,” I devoted much of this month to getting to know this year’s Oregon Book Awards finalists. (Winners were announced April 28).

It’s always interesting to see where the judges and I agree and disagree. I was prepared to not finish “Honey,” a novel by Victor Lodato. I’d read his previous novel, “Edgar and Lucy,” but couldn’t remember a thing about it. Not the most hopeful sign.

But I ended up sticking with “Honey.” Its title refers to the protagonist’s nickname. After growing up in a tumultuous, violent Italian American household in New Jersey (cue the theme music from “The Sopranos”), Honey left for a new life in the art auction world. Now, in her mid-80s, something — regret? vengeance? a need to remember? — has pulled her back to confront her memories.

Honey is alone, having outlived several partners and never having had children. Her remaining relations consist of a middle-aged nephew, his wife and their mostly grown sons, none of whom she much cares for. Her nephew, for one, reminds her too much of her father.

Still, Honey finds a community coalescing around her. Despite their frequent clashes, her nephew and his wife abide by the rule that la famiglia è la famiglia. A neighbor who accidentally runs over Honey’s beloved tree becomes a friend. An artist who comes to her aid after a frightening attack also becomes part of her life. The great-nephew she initially thought was a dangerous drug addict turns out to be fighting a different battle, one she might be able to help with.

I appreciated Lodato’s ability to crawl inside the perspective of an octogenarian woman who has lived both too much and not enough. I hope to have half her tenacity when I’m her age.

“Mischievous Creatures: The Forgotten Sisters Who Transformed Early American Science”

There’s something Brontë-esque about Catherine McNeur’s story of two 19th-century Philadelphia sisters who challenged prevailing scientific notions and, indeed, an entire scientific worldview that women could not be more than amateur dilettantes when compared to “men of science.”

“Mischievous Creatures: The Forgotten Sisters Who Transformed Early American Science” restores Margaretta Hare Morris and Elizabeth Carrington Morris to their rightful places in the scientific annals. Margaretta was an entomologist who helped educate farmers about insect infestations of their crops and orchards. Elizabeth was a botanist who became an expert on local flora.

Attitudes toward them and their work ran the gamut. Margaretta was elected to the American Association for the Advancement of Science and Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences. Elizabeth was known in botanical circles as a careful specimen collector and a skilled illustrator. Yet, having faced backlash and condescension, she often wrote her articles for scientific journals anonymously or under a pseudonym that disguised her gender. Margaretta was allowed to be a member of associations but not to speak or lead.

McNeur gives us not only a detail-rich biography of two pioneering scientists whose lives and works were erased, but also a thorough look at how and why this erasure happened. Thank you to the judges who selected McNeur’s book as an Oregon Book Awards finalist, making sure it too isn’t forgotten.

“I’m Gonna Paint: Ralph Fasanella, Artist of the People”

Anne Broyles’ “I’m Gonna Paint” is a children’s book. But this adult is still thinking about it weeks after reading it.

Broyles’ picture book biography introduced me to American painter Ralph Fasanella, whom the American Folk Art Museum describes as a renowned painter of “social reality.” The son of Italian immigrants, he had a rough-and-tumble childhood that included several years in reform school. But, Broyles said at the Oregon Books Award Ceremony after winning the children’s literature category, he was a voracious reader, and books helped save him.

The son of an ice deliveryman and a dressmaker who published an anti-fascist newspaper, Fasanella became a union worker and organizer. By his early 30s, he was experiencing arthritis in his hands. A co-worker suggested he try painting to ease the pain. He was instantly hooked. He spent the rest of his life creating intricately detailed canvases about everyday work and play.

Illustrator Victoria Tentler-Krylov has complemented Broyles’ affectionately told story with voluminously gorgeous pictures. I found myself Googling “Ralph Fasanella exhibits 2025” and was chagrined to learn I’d just missed a retrospective in New York. My consolation prize was this 22-minute documentary from The Met.

Happy reading!