Bookworm: April 2024

'Our Missing Hearts,' 'The Hive and the Honey,' 'Ho'onani: Hula Warrior,' 'The Refugee Ocean,' 'Moloka'i'

This post contains an affiliate link or links. If you use a link to buy a book, I may earn a small commission. You can find all the books that have been featured in this newsletter in my Bookshop store.

This month’s issue is all fiction — not intentionally!

Table of contents

Dystopian fiction: “Our Missing Hearts,” by Celeste Ng

Short stories: “The Hive and the Honey,” by Paul Yoon

Picture book: “Ho'onani: Hula Warrior,” by Heather Gale

Fiction: “The Refugee Ocean,” by Pauls Toutonghi

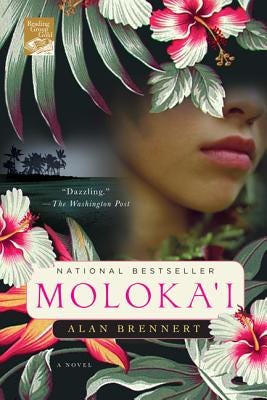

Historical fiction: “Moloka’i,” by Alan Brennert

“Our Missing Hearts”

My neighborhood library branch is closed for renovation, so I’ve been diverted to the next nearest branch. While getting to know its layout recently, I came across a novel by Celeste Ng, “Our Missing Hearts,” that I wasn’t familiar with. I’d enjoyed her other novels (“Little Fires Everywhere,” “Everything I Never Told You”), so grabbed this one.

“Our Missing Hearts” came out in 2022, amid the COVID-19 pandemic and a wave of blatant anti-Asian hate. The novel is set in an America that underwent a years-long economic crisis blamed on China and now lives under PACT, an acronym for Preserving American Culture and Traditions:

A solemn promise to root out any anti-American elements undermining the nation. … Rewards for citizen vigilance, information leading to potential troublemakers. And finally, most crucially, preventing the spread of un-American views by quietly removing children from un-American environments — the definition of which was ever expanding …

The novel’s first section revolves around 12-year-old Bird, who doesn’t remember life before PACT. He does remember his mother, Margaret Miu, a Chinese American poet who left one day three or four years ago and didn’t come back. His white father refuses to talk about her or live in the house they once shared. Bird goes along with this until he receives an envelope, addressed to him in his mother’s handwriting, that contains only a drawing. His search for its meaning leads him away from home.

Meanwhile, anti-PACT protesters have adopted a phrase from one of his mother’s poems: “our missing hearts.” They spray-paint it on streets and create public art around it to keep attention on the children who’ve been taken from their families.

The novel’s second section focuses on Margaret and her and her immigrant parents’ experiences during the Crisis. As I read, I kept thinking of those who’ve suffered terribly from anti-Asian hate in recent years: The eight people, including six Asian women, killed in the Atlanta spa shootings. Vicha Ratanapakdee, 84, killed in California for going for a stroll while Asian. A father and his two sons, ages 6 and 2, punched (the father) and knifed (the children) in Texas for grocery shopping while Asian. Vilma Kari, 65, kicked to the ground and stomped on the head in New York for walking to church while Asian. Michelle Go, 40, killed in New York for waiting for a subway train while Asian. Ng alludes to a couple of these incidents, which for me added a second meaning to the title: Where were the attackers’ hearts?

“Our Missing Hearts” ultimately offers a message of hope, centering on an act of art that appeals directly to the heart. But we don’t get to find out what happens to the artist. Ng leaves it to us to write that ending, to think about whether we would deliver such a message — and accept the consequences.

“The Hive and the Honey”

I always read the acknowledgments. They offer such interesting glimpses into an author’s personality, friends, colleagues, experiences and interests. In the acknowledgments for C. Pam Zhang’s "Land of Milk and Honey,” she makes two mentions of her literary agent, Bill Clegg: once as an individual and one of his eponymous agency. Quite the influence, I thought, and looked him up. Turns out his agency represents several other authors whose books I’ve enjoyed. So down the rabbit hole I went, placing a number of Clegg Agency titles on hold at the library. One of the first to come through was Paul Yoon’s story collection “The Hive and the Honey.”

It’s a slim collection of seven stories exploring the Korean diaspora. Yoon’s protagonists grapple with language and cultural barriers, isolation, doubt and regret. They form and break alliances against the unknown.

As a member of a family tree that’s relatively small — roots in Taiwan, branches in the U.S. and Canada — I have a limited view of the diasporic experience. Yoon paints portraits of it in contexts I had not considered: A once-incarcerated Korean American starting over in rural New York. A North Korean defector in Spain. A Korean couple who grew up together in England.

In “Person of Korea,” 16-year-old Maksim, a second-generation Korean Russian, writes to his long-absent father to tell him about the death of the father’s brother, with whom Maksim has been living. When the father doesn’t reply, Maksim sets out to inform him in person. (He needs to dodge his uncle’s creditors anyway.)

The father-son reunion amounts to little more than a brief exchange before the father gets a call from the prison where he works as a guard, and has to leave.

“Maksim, what was the second thing?”

“The second thing?”

“That you wanted to say to me,” his father says. “You said you came to say two things. What is the second thing?”

Two guards with rifles are in the cab, staring at Maksim.

“Is there anyone else?” Maksim says.

“Anyone else?”

“In our family,” Maksim says. “Is there anyone else, somewhere else?”

Somewhere else: the guiding theme of any diaspora.

“Ho'onani: Hula Warrior”

This month I attended my first-ever ho’ike, or sharing of knowledge. This particular ho’ike was a cultural sharing, featuring about two dozen dances from the cultures that make up Hawai’i.

I didn’t want to walk into the ho’ike completely uninformed. So I browsed the library for books that might help, and came across Heather Gale’s picture book “Ho’onani: Hula Warrior.” Based on the documentary “A Place in the Middle,” the book revolves around a child who dreams of taking part in a big hula performance at school. The catch: This particular hula is typically performed only by boys, and Ho’onani looks like a girl. I say “looks like” rather than “is” because Ho’onani identifies as neither a girl nor a boy, but “in between.” Is this the real reason her sister is so hostile to her ambition?

Mika Song’s illustrations add a lovely poignancy to the story, which Gale tells with a light touch. It’s an inspiring tale of pursuing a dream and claiming a space.

“The Refugee Ocean”

Novelist Pauls Toutonghi, whom I once had the pleasure of meeting, is the American son of immigrants, an Egyptian father and a Latvian mother. His early books mined his personal history, from the novel “Red Weather” (a Latvian American family in Wisconsin) to the novel “Evel Knievel Days” (an Egyptian American family in Montana) to the nonfiction book “Dog Gone: A Lost Pet's Extraordinary Journey and the Family Who Brought Him Home” (an account of the hunt for Toutonghi’s brother-in-law’s golden retriever mix after it wandered off the Appalachian Trail, oblivious to its need for life-saving medication).

Toutonghi’s latest novel, “The Refugee Ocean,” is a variation on the immigration theme. It tells the stories of two musicians who leave their birthplaces for new homes an ocean away — a Lebanese woman rebelling against her subordinate status in the first half of the 20th century, and a Syrian boy fleeing war in the late 20th century.

I kept expecting Marguerite’s and Naïm’s stories to intertwine, but they stay on parallel tracks. In keeping with the protagonists’ love of music, I think of their stories as variations on a classical theme: a brisk first movement setting up the key conflict, a slow second movement in which they ponder the effects of that conflict, a third movement in which they act, and a fourth movement that concludes their story. Throughout, Toutonghi plays on our senses and sensitivities with scenes filled with emotion: a young woman seeing for the first time the much older man to whom she’s been betrothed, a mother and boy flying through the air on the percussive wave of a bomb, a couple falling in love as they roam the city on a surreptitious outing, a hungry teen realizing he’s being denied food because of the color of his skin. Like the best musical compositions, they leave long echoes.

“Moloka’i”

One of the best things about my neighborhood is that it’s dotted with Little Free Libraries, some official, some not. I enjoy seeing all the different styles and am a regular donor and borrower. My most recent find was Alan Brennert’s 2003 historical novel, “Moloka’i.”

Moloka’i is one of the eight islands that make up Hawai’i. When the novel opens in 1891, Moloka’i is the island no one wants to visit. It’s home to a so-called leper colony, where adults and children diagnosed with leprosy live in forced isolation under a local law passed in 1866 as cases surged throughout the islands.

Doctors knew little about leprosy at the time except that it was contagious and had no cure. Its disfiguring symptoms could be frightening:

Through her tears Rachel saw the woman’s face, cratered and oozing pus, and Rachel screamed. In her frantic rush away from the woman she collided with a young girl no older than herself, and she too had a face like a raw wound, and Rachel’s shrieks now seemed to fill the building.

Rachel, a Native Hawaiian, is just seven when her mother notices that the girl doesn’t have any sensation around a cut on her leg — a red flag for leprosy. Soon she also has a sore on her foot that suddenly stops itching. The family tries to hide Rachel’s condition, but her sister blurts it out one day at school. A health inspector shows up the next day, and Rachel’s fate is sealed.

Brennert, who appears to have no personal ties to Hawai’i other than being a fan, did his homework for this book. As he tells Rachel’s story, he adeptly weaves in the fraught history of our 50th state and the successes and failures in treating leprosy as well. He doesn’t hold back from depicting the physical, psychological and social suffering that leprosy can inflict. He also revels in the natural beauty of the islands and the joy of community, especially among those who have been exiled from their first homes.

Thank you for reading Bookworm!

I too always look at the acknowledgments. Looks like I need to get cracking on a couple of these books. Thanks again for the thoughtful clarity of your writing.