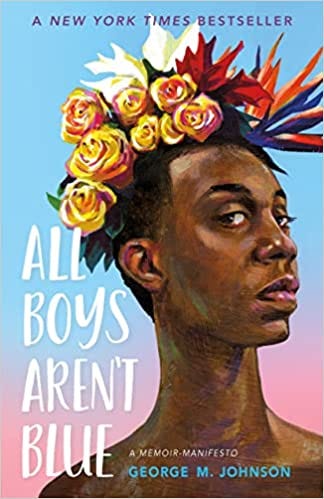

This week I picked up a copy of George M. Johnson’s “All Boys Aren’t Blue” as a nod to the author’s honorary chairmanship of Banned Books Week 2022. The annual observance, which runs through today, is organized by the American Library Association. Johnson’s book is No. 3 on the ALA’s list of the Top 10 Challenged Books of 2021.

***

Johnson’s book labels itself a “memoir-manifesto,” which is an apt description. I might have flipped it around to “manifesto-memoir,” as the book’s emphasis feels to be on the former, but that phrase doesn’t roll as smoothly off the tongue. Regardless, Johnson has written a frank, vulnerable account of one young person’s search for and struggle with identity. What gets me most is that as he grew up grappling with what it meant to be Black and queer, he was doing so within a close extended family that loved and supported its lesbian, gay and transgender members openly and unconditionally — and yet he still didn’t feel comfortable coming out even to those who told him flat out that his sexuality didn’t matter to them.

***

Look at the ALA’s list, and it’s impossible not to notice the high number of books challenged for LGBTQIA+ content or that are by authors of color. Why do such books rouse such a frenzy? Why do any books rouse any frenzy? They’re just books, right? Aren’t we always fretting about how people don’t even read anymore?

Here’s my humble hypothesis: People who challenge books know that books can send powerful messages. Books get inside our heads. We interact with them in a tactilely intimate way, even on an e-reader. That makes for a lasting impression.

Johnson talks in his book about how as a lonely, uncertain child he found refuge in reading. When you see your experiences and identities reflected in the pages of a book, that’s a powerful affirmation that you and your life matter, that you exist. If you don’t want certain people around you and your children, you don’t want them in the books around you and your children, either.

***

Knowledge is truly your sharpest weapon in a world hell-best on telling you stories that are simply not true.

Johnson makes this observation in a chapter about the American history he learned in elementary school, a history that either didn’t make space for Black Americans or put them in a space defined by others. Those efforts to minimize and marginalize are apparent in book banning efforts as well.

We can of course support authors whose books are challenged by buying, borrowing and sharing their work. (Now that I’ve finished my copy of “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” I’m going to offer it to our high school librarian.) But I encourage you to do one other thing as well, and that’s to keep an eye on your local elections. The people who like to ban books know that if they can get onto their town council or school board or library board — you know, those races that might draw 10% voter turnout in an exceptional year — they can control what happens in local libraries. In Mississippi, a mayor withheld library funds over books he didn’t like. In New Hampshire, a city councilor and state senator attempted to ban books he didn’t like. Those are just two examples from this year.

Know what’s happening in your local elections. Then reject the stories that are simply not true.