'A Shrug of the Shoulders': A lesser-known Japanese American story

When Japanese Americans were swept off the West Coast during World War II, not all ended up in incarceration camps.

This post contains an affiliate link or links. If you use a link to buy a book, I may earn a small commission. You can find all the books that have been featured in this newsletter in my Bookshop store.

Japanese American history has been at the forefront of my consciousness lately.

Last month, I was among several hundred people who attended a memorial for Henry Fuhrmann, a Japanese American journalist and educator. He made a bit of journalistic history when his essay “Drop the Hyphen in Asian American” persuaded a number of news organizations to do so, including The Associated Press, whose articles are published worldwide. Before Fuhrmann’s death from cancer last September, he scheduled his memorial for the Japanese American Day of Remembrance, Feb. 19. It marks the date when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 and set in motion the mass imprisonment of Japanese Americans living on the West Coast during World War II.

Fuhrmann also had thoughts about the language around that period of history. It’s commonly called “internment,” a word Fuhrmann argued is euphemistic and incorrect. He preferred “incarceration,” and this month The Los Angeles Times, where he was once a top editor, announced that going forward, it will use that term. “We are taking this step as a news organization because we understand the power of language,” Times Executive Editor Kevin Merida said in a statement.

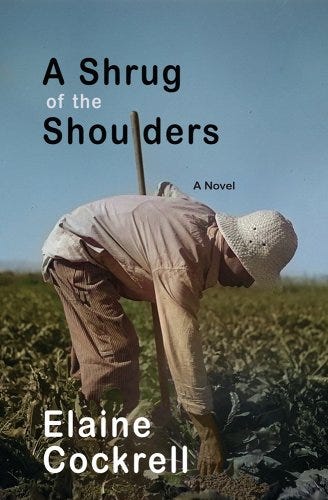

That’s the context for my musings this week about “A Shrug of the Shoulders,” a novel by Elaine Cockrell. I’ve read a number of books about Japanese American incarceration (see below for a list), but this is the first one I’ve read about a corollary experience: that of Japanese Americans who went to Eastern Oregon to fill a wartime labor shortage and avoid the prison camps.

Cockrell grew up in an agricultural community in Eastern Oregon that included Japanese American families. In her novel, she interweaves the stories of four characters: Two often at-odds Japanese American brothers whose family has to leave their Washington farm, a Japanese American girl whose family is uprooted from their Oregon home, and a white teenager in Eastern Oregon whose community debates whether to hire Japanese American workers. As the Japanese Americans cope with incarceration — they’re sent first to a livestock pavilion-turned-“assembly center” in Portland, then to Camp Minidoka in Idaho — the Eastern Oregon community reluctantly decides it can’t afford to turn down any help to bring in its sugar beet crop.

One character, George, uses this need to his advantage by taking a job as a recruiter — his employer recognizes that Japanese American workers are more likely to respond positively to him than a white man. George is thus able to escape the camp where his family is sent, but is wracked with a version of survivor’s guilt. His story, I was interested to learn, is rooted firmly in Oregon history; I learned more about it in a digital exhibit on the Oregon Secretary of State website.

While the farm community needs the workers, that doesn’t mean they get a warm welcome. One local woman in particular is incensed by their presence: She’s sent two of her sons to the war, and one doesn’t come back. To her, these people look just like the enemy, and in her grief she can no longer distinguish between them.

If you’re interested in this period of history, I recommend these titles that I’ve read:

Nonfiction:

“Stubborn Twig: Three Generations in the Life of a Japanese American Family,” by Lauren Kessler. This book tells the story of the Yasui family, including Minori Yasui, an Oregon lawyer who fought a World War II-era curfew for Japanese Americans all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and posthumously received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. (His prison cell is preserved, along with an audio recording of him, at the Japanese American Museum of Oregon.)

“Facing the Mountain: An Inspiring Story of Japanese American Patriots in World War II,” by Daniel James Brown. This exhaustively researched book is a thoroughly engrossing deep dive into the lives of several Japanese American soldiers in the storied 442nd Regiment and the families they left behind.

“We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Wartime Incarceration,” by Frank Abe, Tamiko Nimura, Ross Ishikawa and Matt Sasaki. The conventional depiction of life inside the camps is one of stoic resilience: sock hops, baseball teams, gardens, wood carving. This book rebuts that narrative, using a graphic novel format to tell the stories of three Japanese Americans who wouldn’t accept their new circumstances.

Fiction:

“Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet,” by Jamie Ford. A budding romance between a Chinese American boy and a Japanese American girl in 1940s Seattle is interrupted when her family is incarcerated.

“This Light Between Us,” by Andrew Yakuda. A bit of magical realism infuses this story about a Japanese American boy on Washington’s Bainbridge Island and his pen pal, a Jewish girl in France, both trying to cope with having their worlds turn against them.

For kids: “Dash,” by Kirby Larson. When grade schooler Mitsi is sent with her family to an incarceration camp, the part that hurts most is having to leave her dog, Dash, behind.

Dear Amy Wang, thanks for this bookworm newsletter. (I'm glad we didn't lose your book musings when you left the Oregonian.) And thanks for the recommendation of Elaine Cockrell's book. I've read all the other excellent volumes you recommended about this shameful episode in U.S. history, and now I'm going to add Cockrell's book to my "gotta read" list.

I'd like to add a couple more suggestions about this important topic, both from our state's own one-time Poet Laureate Lawson Fusao Inada, who was incarcerated as a child with his family in camps in Arkansas and Colorado. In 1992, Inada's poetry collection Legends from Camp was published. It won an American Book Award and has a bunch of poems about his experiences as a kid in those camps. And in 2000, Inada edited a powerful anthology, Only What We Could Carry: The Japanese American Internment Experience, which spotlights in multiple voices and forms all aspects of that historic injustice. I highly recommend both.